When I first watched Dead Poets Society on a monotonous November evening, I remember feeling so moved that I couldn’t stop thinking about it for days on end. I remember wishing for an alternative ending, resonating with many motifs, and bringing it up in every conversation. But most of all, I remember feeling called to create. That is when I realised this film wasn’t meant for sole entertainment — it demanded close reflection and analysis. There are very few pieces of art that wield the power to influence entire generations of humanity. However, “no matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world”. Perhaps Dead Poets Society is the epitome of this concept.

Tragedy

In his essay Tragedy and the Common Man, Arthur Miller argues that the “common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were.” This is seen explicitly in his play Death of a Salesman (DOAS), which will be referred to numerous times here in comparison to Dead Poets Society (DPS). In Death of a Salesman, the audience follows the tragic arc of the Loman family, especially Willy Loman. The play ends in a similar tragic outcome to Dead Poets Society, with Willy Loman, our tragic hero, taking his own life as a result of his impossible chase after the American Dream. I propose the argument that Neil Perry is a tragic hero as well.

Miller argues that tragedy “is the consequence of a man’s total compulsion to evaluate himself justly.” This clearly relates to Neil, as he attempts to find out, “for the first time,” what he “really wants to do,” and what’s “inside” of him. When this is suppressed by the conservative elements of society — namely Neil’s father (Mr. Perry) and the broader education system at Welton (which serves as a microcosm for modern capitalist society) — Neil takes his own life, as he cannot make it ‘extraordinary’.

However, the notion of the American Dream is further layered in Dead Poets Society. It could be argued that Neil is different from Willy, as it is fighting against the American Dream that finally kills him. Willy is metaphorically and literally driven to the peak of madness when he realises that he will never achieve the American Dream, for it is an unattainable ideal. Neil’s suicide is a result of many different factors, the core of them being that he will never find his place in the present society. This comes from a place of alienation, where he is reduced to a mere appendage to the machine, as are the other Dead Poets: the “future lawyers” and “future bankers.”

The link between Death of a Salesman and Dead Poets Society is further amplified by Collins, who highlights Miller’s argument that “acting on a stage must be an overflowing of love.” He further links this to Weir’s “dramatic emphasis on spell-like music, the enchanted wood, and Puck’s magical role in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

The Tragic Hero

Neil’s hamartia (fatal flaw) as the tragic hero is his blindness. Neil represents the Romantic dream — an idealist, passionate about nature and finding his purpose outside of the echo chamber that is capitalist society. We see this numerous times, the earliest example being Neil thinking he can “reconvene” the Dead Poets Society, that “nothing’s impossible,” with his unfettered faith in Carpe Diem.

The original screenplay for Dead Poets Society involves a crucial scene where Neil enquires about the meaning of “dead poets.” To this, Keating responds that “to join the organisation, you had to be dead… Full membership required a lifetime of apprenticeship. The living were simply pledges”. This alludes to the macabre idea that an essential part of Romanticism was formed of alienated members of society who had ‘died’ metaphorically, and could no longer wilfully participate in the rat race.

However, this suggests a common idea that echoes around similar texts, thereby foreshadowing the tragic outcome. In Death of a Salesman, Willy tries to achieve his romantic ideal of connecting with nature whilst pursuing an unattainable capitalist dream (“Me and my boys in those grand outdoors” / “Get out of these cities… for a fortune up there”). This only acts as a catalyst for his tragic fall.

In both cases, this false idea of romanticism co-existing within the current societal structures leads to tragic outcomes, namely the characters’ deaths. Dead Poets Society doesn’t dissent from this interpretation, as Neil’s naivety is rebutted by reality, symbolised by Mr. Perry. This is shown clearly towards the end, when he comes out smiling on stage, expecting a proud father, only to be met by Mr. Perry’s cold stare. This suggests that one cannot inhabit romantic ideas within the current norms we abide by.

Nietzsche’s idea of tragedy originating from the conflict between Dionysian (emotion, ecstasy, chaos) and Apollonian (order, logic, structure) can also be applied to Dead Poets Society. Tragedy, interpreted in this way, is therefore not a resolution but an expression of the sublime — terrifying and beautiful. In all cases, the audience is shown a glimpse, an alternative ending of what could have happened: Neil’s sigh of relief backstage, Willy’s ecstasy in nature, Lear’s catharsis in being reunited with Cordelia. However, the final resolution remains that an attempt to do so would only lead to tragic outcomes.

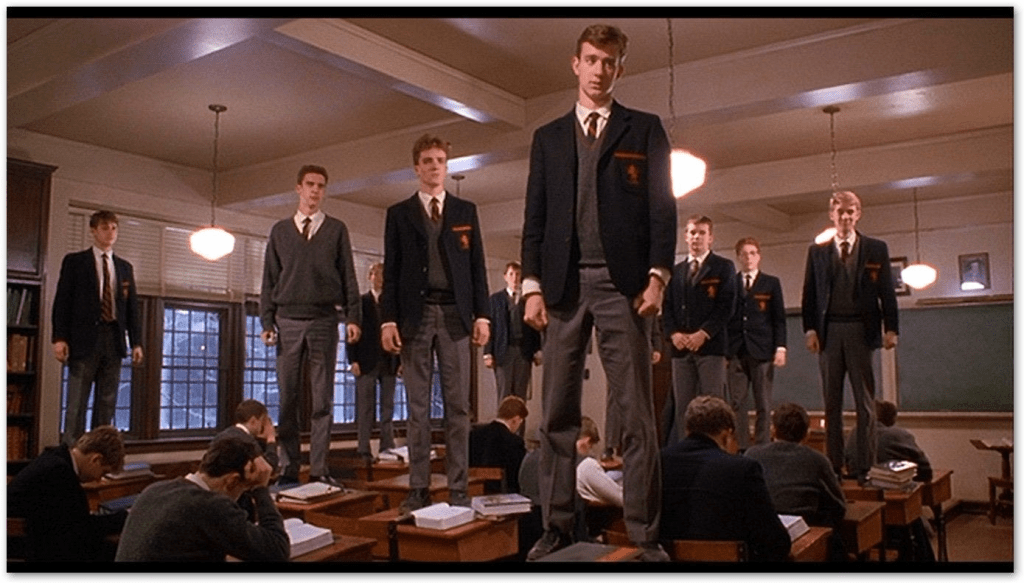

This is primarily why Keating’s “Carpe Diem,” against the setting of an orthodox boarding school and an adamant capitalist society, falls short in the end. However, Dead Poets Society doesn’t offer merely a bleak ending. It subtly challenges this idea, as clearly shown in the ending scene, where half the classroom is up on their desks for Keating and the other half turns their backs on him. This idea is explicitly expressed in the original screenplay, where Keating was originally meant to say, “Wonderful things are possible if we only dare dream them, boys.” The final frame of partial revolution, coupled with the heroic background score of bagpipes and trumpets, as if it were Judgement Day (Keating’s triumph), seems to leave the audience with a final message: all is not lost. One cannot uproot an entire societal structure with a single poem; however, continuous acts of subtle rebellion and courage have the power to significantly alter the world.

Neil is also very similar to Biff, and the father-son dynamic between Biff and Willy mirrors that between Mr. Perry and Neil.

“I think if he finds himself” / “Biff Loman is lost. In the greatest country in the world a young man with such personal attractiveness gets lost.”

Willy, too, has high expectations from his son, is “counting” on Biff to retire him, and views his own son as a product of capitalist society. His priority for his children is not their happiness. He subjects Biff to what will sustain him in the short term, instead of long-term serenity.

This is seen in Dead Poets Society as well, especially in the interactions between Neil and his father:

MR PERRY

After you’ve finished medical school and you’re on your own, then you

can do as you damn well please. But until then, you do as I tell you.

Is that clear?NEIL

Yes sir. I’m sorry.MR PERRY

You know how much this means to your mother,

don’t you?

NEIL

Yes sir. You know me, always taking on too much.

Biff, himself, mirrors Neil in many ways. Biff, too, seeks an unconventional life ‘on the farm’, outside the city. He seeks a Romantic dream that can never be achieved in the place he’s in. Biff, too, is ‘trapped’ and doesn’t know ‘what the hell he’s working for’. However, there is one stark difference between the two — one that significantly sets their fates apart.

At the climax of Death of a Salesman, we witness Biff finally standing up for himself and the broader Romantic movement by speaking the truth:

“No you’re going to hear the truth – what you are and what I am /the man don’t know who we are…we never told the truth for 10 minutes in this house.”

Biff shows Willy his reality, that he was “never anything but a … dollar an hour”. Similarly, in Dead Poets Society, when Neil finally gathers the courage to tell his father ‘how he feels’, the audience expects a dramatic monologue tying together all loose ends of the story. Instead, we see Neil tragically resign to his fate with ‘nothing’. ‘Nothing’, in this sense, being ironically similar to Biff’s dramatic revelation that he is “nothing”.

This leaves Neil with an incomplete catharsis, though he had his anagnorisis at the play. This renders Dead Poets Society somewhat anti-climactic, all whilst leaving the audience wondering what could’ve happened, had Neil spoken up. In the end, Neil fails to do his soul poetic justice, which ends up killing him. This is where he significantly differs from Biff, who found his voice.

Furthermore, I believe Dead Poets Society also reveals a wheel of fortune. Neil plays the classic tragic hero; at the beginning, he’s immediately perceived to be charismatic and “one of Welton’s best”. However, this only deteriorates as the story progresses, and his death arguably establishes his status as the tragic hero. Todd Anderson juxtaposes Neil’s arc. At the start, Todd is notably different from the other boys— both metaphorically, with his shyness, and literally, as we see him being one of the only ones not to wear a Welton blazer. Whilst, in the end, Neil resigns to his fate with ‘nothing’ and loses his voice, Todd gains his ‘barbaric yawp’ by standing up on the desk in the final scene, reciting:

“O captain, my Captain”.

These juxtaposing character arcs reinforce the tragedy of Dead Poets Society, whilst also alluding to the biblical phrase “the meek shall inherit the Earth”.

One argument against Romanticism, and thereby Keating’s teachings, is also rooted in the analysis of Dead Poets Society as a tragedy. In King Lear, Lear’s attempt to make sense of the absurdist cosmos leads him to madness, and ultimately to his existential crisis and death. This suggests very strongly that mortals shouldn’t attempt to exceed their epistemic reach, as it would only lead to madness. This could arguably suggest that Keating’s attempt to influence a class of 17-year-old boys was dangerous, and ultimately led to the tragic outcome.

Bauer argues that “Keating’s individualism is just another brand of authoritarianism”. However, I believe that it is not Keating’s ideals that led to the tragic outcome, but the mere incompatibility of those ideals with the current society that sets the tragic fate. This also shows the incompetence of adults, such as Neil’s parents as well as Mr. Nolan, in providing the young with a safe space to pursue their purposes. Throughout the film, they instead subject them to pragmatism, stripping them of their individuality.

Keating, too, can be seen as a tragic hero, albeit to a lesser extent than Neil. Keating is the epitome of Romanticism, hence the similarity with the name ‘Keats’. He is shown as a natural leader and someone unconventional who challenges societal norms. Keating is an ideal whom Neil, along with the other Dead Poets, look up to.

Muro argues that “the students even worship him, linking here the metaphor of the Captain of the ship to a possible understanding of Keating as a God figure”. This is seen numerous times, but the most potent moment is when Neil opens up to Keating about his passion for acting and his father’s disapproval of the ‘acting business’. Neil asks Keating how he can “stand” being at Welton, despite having the freedom to “go anywhere”. To this, Keating responds he ‘loves teaching’ and wouldn’t be “anywhere else”.

This highlights the juxtaposition between Keating and Neil; despite looking up to Keating and being a natural leader like him, Neil still feels further away from him because of his unfulfilled passions and ambitions. However, Keating’s fatal flaw perhaps lies in his hubris. His unfettered belief in Romanticism is misinterpreted by some students, though he clarifies his intention later by reprimanding Charlie. The consequences can be seen in Charlie’s ‘lame stunt’, as well as Neil’s act of committing suicide, which some critics argue was his interpretation of Carpe Diem — his final act of rebellion, his final attempt to seize the day. Whilst Keating receives a heroic final scene, it is his ultimate powerlessness that is highlighted against the Welton establishment, which casts him as the scapegoat.

In describing the Trickster, Callahan argues that:

“the Trickster disrupts our lives and won’t let us settle into a routine that, however comfortable it might be, is really a rut.”

He adds that this is the person “who pushes the hero into action”. I believe this can apply to either Keating or Neil, as it is both their sacrifices that lead to Todd’s awakening — who can perhaps be seen as the main hero of this film, as will be explored later.

The Tragic Night

Another important criterion Miller raises is the tragic night, which he describes as ‘a condition in which the human personality is able to flower and realize itself’. This essentially relates to anagnorisis in classical tragedy. Miller asserts that the ‘wrong is the condition which suppresses man’, and the tragic outcome is a subsequent result of ‘the thrust for freedom’.

As a result, ‘the commonest of men…throw all he has into the contest, the battle to secure his rightful place in his world’. In Death of a Salesman, this relates to the final scene where Willy drives to his own death:

”there is the sound of a car starting and moving away at full speed”.

Onstage with the imaginary brother who abandoned Willy for wealth, Willy chooses to abandon his family for wealth through the life insurance policy. This reflects Willy’s warped sense of the American Dream, as he is unable to see his worth beyond monetary terms.

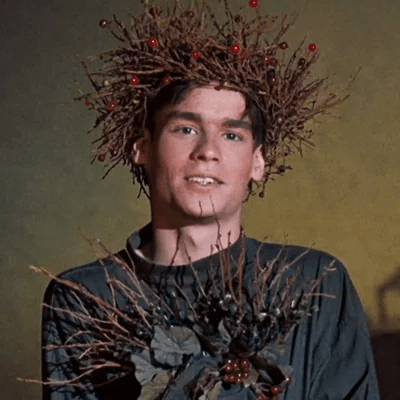

In Dead Poets Society, this criterion can be seen in Neil’s act of suicide, which can be carefully interpreted as his final attempt to regain agency. This is seen in the final shot, where he wears Puck’s crown — a symbol of freedom and identity — and stares outside at the purity of the snowy night, half-naked yet connected to Nature like a true Romantic. Muro proposes that “Neil’s body is presented as a site of vulnerability”. The original screenplay amplifies this idea. Originally, Neil’s suicide scene was meant to parallel the scene where the Dead Poets hold their last meeting. The night is described as a ‘full moon’, whilst the ‘stars are out’ and it is ‘clear and cold… Mother Nature has covered the world with sparkling diamonds’. This is ironic: Neil’s death and final act of tragic rebellion come at a time when Nature has regained control over Earth, with Winter symbolising rebirth. Neil therefore reaches the peak of his Romanticism and is ‘reclaimed’ by Nature, away from the man-made world of greed and unattainable social ladders.

Whilst Neil prepared for his final rebellion, the film was meant to draw a parallel with Keating’s poem to the boys, with the repetition of “Are you washed in the blood of the Lamb”. Just as Neil pulls the trigger, Keating and the boys chant “Alive, Alive” in unison to the Heavens.

This scene does two contrary things. Firstly, it idolises Neil Perry as a Christ-like figure, presenting him as the sacrificial lamb. Indeed, he can be seen as a sacrifice — it is only after Neil’s death that Todd gains his voice, and the Dead Poets are almost immortalised, with Keating’s heroic partial triumph. Secondly, it highlights the ironic powerlessness of the Dead Poets. Whilst, in the quiet of the night, they participate fully in Romanticism and realise their individuality, Neil’s parallel morbidity undercuts the romantic heroism with realism: a melancholic undertone that suggests Romanticism is an idealistic, powerless movement that will always be undermined by the stark realism of the world.

Classical Tragedy

Whilst Dead Poets Society satisfies Miller’s common tragedy and is similar to Death of a Salesman, it is interesting to consider how far it fits classical tragedy. Aristotle argued that the most important part of a tragedy was its plot, and that it came before character. This seems to suggest that the character is almost driven by his fate, which forms the doomed plot of the tragedy, leading to inevitable outcomes. This can certainly be seen to some extent in Dead Poets Society with the lack of agency in the protagonist, Neil. However, this notion is largely undermined by the various acts of rebellion — by the Dead Poets, by Neil himself, McAlister’s acknowledgment of Keating’s unconventional teaching methods, and in the final scene where half the class stands for Keating. This takes a nuanced approach, leaving the characters with some sense of agency in the end, even though it is constantly undermined by the bureaucratic establishment of Welton as well as tradition.

Aristotle argues that characters must be “good or fine”, “fit” or true to type, “true to life”, “consistent” with themselves, “necessary”, and “beautiful, idealised”. Characters from Dead Poets Society linger in this space; whilst many of them are idealised with religious and Romantic imagery, as has been mentioned before, it is hard to fully assess them as consistent or warrior-like — though that renders them realistic and “true to life”. Aristotle also highlights the importance of musical elements in tragedy, which can clearly be seen in the soundtrack for DPS — such as the chorus during football training and the heroic sound of bagpipes in Keating’s triumph, all of which further romanticise the Dead Poets and heighten the tragedy.

Romanticism

“I went to the woods because I wanted to live deliberately. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life. To put to rout all that was not life, and not when I had come to die, discover that I had not lived.” – Thoreau

Muro argues that the realism–romanticism battle is seen in the characters’ struggle against reality. She argues that Neil fights “between dreams and reality, between his daydreams of becoming an actor and his father’s down-to-earth plans for his son to become a doctor.” In relation to Todd’s character struggle, “unlike Neil, he is insecure about his own self and he will try to find his identity throughout the movie.” Todd’s “sweaty-toothed madman,” Muro argues, can be interpreted as “a representation of reality, of the expectations that are built upon him. It does not matter what he does, it will never be enough — and this could be applied to Neil as well.”

However, the dangers of these two extremes can clearly be seen in Neil’s illusion. On the one hand, he is “trapped” in the real world, acting as a “dutiful son” for his father. On the other hand, he craves to “live dozens of lives” and “not, when he comes to die, discover he has not lived.” In both cases, however, Neil is eternally acting, entrapped on different sides of the same illusion. This highlights his fatal flaw — his blindness, suggested literally when he closes his eyes in the final scene against the window.

Neil’s vulnerable stance, half-naked with Puck’s crown, can be interpreted as his attempt to reconcile with nature and his Romantic ideals. His fatal flaw also highlights tragic inevitability — much like Willy Loman will always remain a “Low Man”, it was fated for Neil Perry to “Perish” in the end. This idea is foreshadowed in his speech as Puck:

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended—

That you have but slumbered here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend.

If you pardon, we will mend.

And, as I am an honest Puck,

If we have unearnèd luck

Now to ’scape the serpent’s tongue,

We will make amends ere long.

Else the Puck a liar call.

So good night unto you all.

Give me your hands if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

Essentially begging forgiveness from the audience, Puck promises to amend the play and insists that it was only a dream, not reality. This draws a metaphorical comparison to Neil’s own situation, leaving a fatalistic suggestion that all the Romanticism, idealism, and poetry experienced by the audience up to this point was only an illusion, waiting to be ‘mended’ by reality.

This idea is also symbolised by the cave in which the Dead Poets seek refuge. The cave is eerily similar to Plato’s allegory of the cave. In Plato’s cave, people only see shadows on the wall. These shadows link to individual objects in the world, whilst the objects represent ideas rooted in reality. This serves as a metaphor for present society, which is built on the notion that these shadows are the only reality. In essence, the shadows are only an illusion, keeping people trapped in “false consciousness.”

With this interpretation, it could be suggested that the cave in Dead Poets Society was only an illusion — a mere momentary escape from the cold, brutal realities of the world. The cave represents an alternative ending, one of harmony and idealism. However, this illusion is quickly brought to an end with Neil’s death, reinforcing the stark realism of the outer world. In this sense, Neil’s death is as metaphorical as it is literal: it symbolises the suppression of Romantic ideals and the loss of individuality.

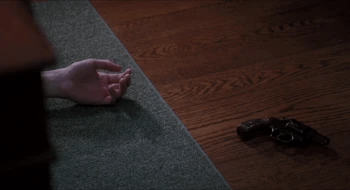

For the audience, Neil’s death happens off-stage; we only see the aftermath. This romanticises him as a figure who leaves a grave impact — highlighted literally through his father waking from the sound of the gunshot, and metaphorically through Todd’s awakening. Up until this point, Neil’s father has been painted as a stoic figure, almost indifferent to his son’s happiness. Neil’s death adds nuance to this otherwise flat character, as he displays devastation through the repetition of “my son, my son.” This suggests a fatalistic element: Neil dies only as his father’s son, despite the many dreams he had and the many “dozen lives” he aspired to live.

The fact that we only see Neil’s fallen hand, and not his entire body, highlights both the loss and the gain of agency. Neil’s physical fall also alludes to the story of Icarus. Like Icarus, Neil flies too high, and these heights result in his tragic fall. Perhaps the tragedy of DPS is that Neil is briefly shown a glimpse of the life he could have had, only for it to be brutally seized from him by reality. Cross argues that “Neil Perry experiences a horrifying dread of disobeying or displeasing his father, but an even more horrifying dread of not trying to accomplish his own, rather than his father’s dreams. This conflict leads Neil to commit suicide.” In contrast, Muro argues that “even if the audience views Neil’s suicide as a sign of an unhappy ending, it represents Neil finding his true voice and his identity as a romantic.” Neil Perry therefore serves as a larger allegorical reference to the entire clash between romanticism and realism, and the ‘fallen’ souls that find themselves entrapped between the two.

Welton and the traditional parenting style in this film represent the opposite of Romanticism — realism. The archaic and conditioned emphasis on ‘tradition, discipline, honour and excellence’, and the autocratic control of parents over their children’s futures, serves as a microcosm for broader capitalist society — one that tames students in the same way and builds them all to become part of the same herd, serving the same machine.

This is perhaps why literature is chosen as the medium for rebellion in DPS. “Medicine, law, business, engineering, these are all noble pursuits, and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.” Literature has historically been used as a medium of rebellion — by both the elite and the common man. Literature has also been the first to be taken control of under any new authority, for it awakens souls and makes them realise the illusions they are entrapped in. In medieval Europe, literature was rare and handwritten, largely under the control of the social elite such as the Church and members of the clergy, with everyone else forbidden from reading. This pattern repeated in the 19th century, with enslaved Africans in America being legally banned from learning to read. Censorship of literature was an important part of Stalin’s Soviet Union, Mao’s China, as well as Hitler’s Nazi Germany. This idea is exemplified by Frederick Douglass: “The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers.” Literature turns mere appendages and ‘slaves’ into free thinkers, which was one of Keating’s main aims: to teach the boys how to ‘think for themselves’. Can one really conclude that it was Keating’s aim to radicalise junior classes into a Romantic revolution? It is only half the class that stands up for Keating, whilst the others choose to sit. The entire class had learned to think for themselves — Keating’s greatest lesson. Muro argues that “the battle between romantics and realists is made completely clear… some standing on their desks, face up, versus those who remain seated, unable to look up… we see Mr. Keating from a high-angle shot, from the perspective of the Romantics… the audience is linked to the Romantics.”

Between these two extremes — the realist Welton organisation and Neil’s Romanticism — Todd can perhaps be interpreted as the balance, and the paragon of Keating’s teachings. He sucks out the ‘marrow’ of life without ‘choking on the bones’. The distinction between Welton’s strict authoritarianism and Keating’s pedagogy is highlighted in McLaren’s analysis that “as Keating tempts the students to follow him into the hallway, they look at one another in puzzlement… wait for a bell to signal their next move — the same bell which tolls for Neil, whose tragic death is only one of many deaths in the film.” In this sense, the classroom equates to an “official society where resistance occurs in the cavities that separate the real from the possible”. This amplifies poetry’s power by shifting it from mere words in a textbook to something “their bodies are made to relate to”.

Critical theories

Feminism and Post-colonialism

Applying a feminist lens to DPS highlights many other concepts beyond Romanticism and tragedy. Indeed, in both DOAS and DPS, women are treated as the Other and reduced to mere props. In DPS, this phenomenon can be seen through Chris, who is subjected to the male gaze by Chet and Knox. Chris carries no autonomy and is dehumanised as something Knox “must have”. Neil’s mother also lacks agency, as her voice is constantly overpowered by Mr. Perry. This is similar to the dynamic between Linda and Willy, whose voice is “subdued”. The audience senses Mrs Perry’s genuine, ominous concern for Neil through her suppressed crying and her attempt to comfort him by kneeling behind him. This, however, is undercut by the more oppressive, patriarchal force of Mr. Perry. This chauvinist phenomenon is also noted through Keating’s teachings, such as when he jokes that the purpose of communication is to “woo women”. Women are isolated from literature and education in general, exemplified by Gloria and Tina not being able to recognise Charlie’s plagiarised poems.

If Welton serves as a microcosm for larger capitalist society, it also highlights how women are excluded from it by not being able to participate — Welton being an all-boys school for the elite. This is perhaps accurate for the 1950s. This also relates to Simone de Beauvoir’s criticism that “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”. Giroux argues that “resistance, knowledge, and pedagogy come together in Dead Poets Society to harness identity and power to the misogynist interests and patriarchy”.

Toxic masculinity is also a concept central to DPS, and is directly linked to the arcs of Todd and Neil. Whilst Todd begins timid and is portrayed as almost feminine due to his weakness and submissiveness (“Mr. Anderson thinks that everything inside of him is worthless and embarrassing”), Neil is presented as stoic and traditionally masculine. This is expressed clearly by Todd, who confronts Neil as he tries to force him to speak in the society meetings (“You say things and people listen / I’m not like that”). However, as the story progresses, and as both Welton and Mr. Perry force masculinity upon Neil, he withdraws towards a more feminine character arc. Muro argues that “Neil’s relationship with Todd results, through Neil’s death, in Todd’s successful entrance into manhood”. This is similar to Willy’s attempt to force masculinity upon Biff (“three great universities are begging for him… sky’s the limit… the wonder, wonder of this country”).

Though Keating is idealised, he too is not alien to toxic masculinity. His dehumanising remark to Todd — “are you a man or an amoeba?” — reinforces the same idea of masculinity that sustains oppression and patriarchy. Neil’s femininity is also subtly exemplified by the fact that he plays the role of Puck. Anderson argues that Neil plays the “most effeminate male character in the show”. Cantwell further proposes that “if this were just a story about Neil wanting to be an actor, he would’ve been cast as Hamlet… and then a happier ending”. This suggests deeper problems that DPS subtly hints at, such as the institutional repression of personal identity and intimacy. Neil’s exploration of feminine elements — common to Romanticism — is immediately suppressed by his father, who urges withdrawing him from Welton and admitting him to military school, another symbol of a chauvinist, stereotypically masculine environment. Perhaps the fact that Neil ‘loses’ (dies) and Todd ‘wins’ (becomes the main hero) is fatalistic — as the masculine elements are sustained, whilst the feminine falls.

Similar to how women are treated as “the other,” there is also an element of post-colonial criticism present in the film. Nuwanda represents Charlie’s alter ego and his response to the fact that he has no identity, that he has “never been alive… risking nothing” (original screenplay). While Nuwanda can be seen as Charlie’s rebellion, he is also attempting to be “the Other.” While he has the privilege and position to experiment with his identity, the “Others” do not. This highlights Charlie’s ignorance, even while being Nuwanda. The idea of being “the Other” is romanticised, rather than acknowledged for its alienation.

Marxism

Applying the Marxist critical theory to DPS deepens its reading. “Minds aren’t free; they only think they are.” This idea certainly applies to DPS. We become alienated from ourselves, and under these conditions, material forces influence the internal — the mind — which becomes a form of control. In DPS, Welton and traditionalism control the minds of its students, moulding them into subservient members of society, like all previous generations. This develops into a vicious cycle that entraps generations and kills artistic, free thinking. Similar ideas were explored in DOAS (“Shipping clerk, salesman, business of one kind or another” / “ways to get ahead of the next fella” / “and I saw the sky” / “all I want is out there… who I am”).

This idea can also be seen in the setting of DPS. Just as DOAS being set in the 1950s reflects a time of the American Dream, upward mobility, and consumerism, DPS being set in 1959 symbolises a changing time period, suggesting a transitional moment before a new decade begins. Indeed, most of the film is about change and the process of transition — transitioning ideas, education, passions, and power. The 1950s are historically a time when conformity pervaded American culture, settling for a ‘good life’ that included standards such as marriage and securing a respectable job. In stark contrast, the 1960s are remembered as a time of social change, marked by protests for civil rights and against various injustices in society.

Most of the film takes place within Welton’s grounds. Though covered with beautiful scenery, this only disguises the soul-sucking regimentation happening inside the school. This represents broader capitalist society: though it looks luxurious and welcoming from afar, it enforces a highly regimented lifestyle disguised as financial freedom. As argued by McLaren, Welton’s “natural surroundings point to the unnaturalness”.

“The trees, ponds, and wildlife which canopy the school grounds mask Welton’s manufactured and instrumental education.” This stands in stark juxtaposition to the theatre and the cave — spaces away from Welton that represent subtle rebellion and unity with nature. It is no surprise that these are the places where Neil feels most aligned with himself, unlike the regimented spaces of Welton and his own home, which is introduced with a framed picture of Neil and his parents, looking astray and controlled.

This is similar to the realism–Romanticism debate, in which excessive, indulgent capitalist forces constantly compete against the more meek, non-privileged sections of society. Marxists argue that age stratification is a form of social control, forcing the young to be dependent on adult males and preparing them for the job market. This idea can be seen in both Welton and the parental figures. Both essentially train students to become future lawyers, doctors, and bankers from Ivy League universities. The isolated setting of Welton further alienates its students from comfort and a sense of being. This is especially brutal for the seventh graders at the beginning (“A bell tolls. Parents begin wishing their boys farewell”).

The rigid control at Welton exemplifies constant surveillance, similar to the concept of Big Brother explored in George Orwell’s 1984. Scrutinisation and control can also be interpreted as a literary manifestation of the Panopticon. Originating from Jeremy Bentham’s design, this prison structure involves a central tower surrounded by cells, allowing for constant surveillance. Bentham describes it as:

The Building circular – an iron cage, glazed – a glass lantern about the size of Ranelagh – The Prisoners in their Cells, occupying the Circumference – The Officers, the Centre. By Blinds, and other contrivances, the Inspectors concealed from the observation of the Prisoners: hence the sentiment of a sort of invisible omnipresence. – The whole circuit reviewable with little, or, if necessary, without any, change of place.

— Jeremy Bentham (1791). Panopticon, or The Inspection House

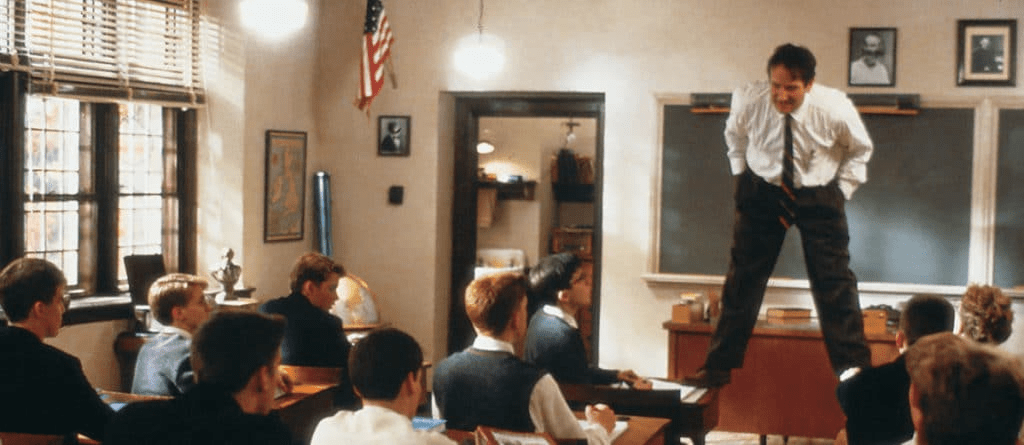

Though it is not practical for a single guard to see all the cells simultaneously, the fact that inmates have no way of knowing when they are being watched instils a fear of constant surveillance. This mirrors the regimented life at Welton, which more broadly represents a society built on scrutiny and adherence to norms. This surveillance is challenged by Keating, who “crouches on the ground whereas the students remain standing and looking downwards at him, thereby suggesting a disruption of their relationships vis-à-vis the body” (McLaren).

Marxists argue that the purpose of education is to legitimise and reproduce class inequalities by forming a subservient workforce. This is evident at Welton, where students from wealthy families are groomed to enter even wealthier sectors of society, perpetuating elitism. This idea is explicit in Neil’s assertion that they are not “a rich family like Charlie’s” and that his parents are “counting on” him. In this sense, Neil and his family become the Others. Giroux notes that “Neil Perry comes from a family that is lower middle class; his father constantly justifies his own imperious manner by arguing that he wants Neil to have the education and social status he never had the chance to experience… Neil in this context becomes the Other, the class-specific misfit who lacks the wealth and privilege to take risks”.

Mr. Perry is blinded to Neil’s reality — to “what his heart is” — by material and societal pressures. To some extent, the audience can sympathise with Mr. Perry. The story is set after World War II, and he belongs to a generation shaped by the Great Depression, where financial stability equated to survival. Neil does have “opportunities” his father “never even dreamt of”. However, the core issue is projection: Mr. Perry imposes his fears and experiences onto Neil, who lives in a different historical moment — a transitional point between the late 1950s and early 1960s. Acting is not a “whim” for Neil; it becomes an essential part of his identity. Once stripped of this identity, Neil finds no purpose in life, leading to the final tragedy.

This also relates to Camus’ absurdism: we live in a meaningless universe, yet must create meaning regardless. Acting represents Neil’s attempt to construct meaning. When this is suppressed, Neil descends into an existential crisis, resulting in his death. This encapsulates Marxist literary criticism: capitalism promotes an unattainable American Dream, one that is privileged over human creativity, individuality, and nature. Neil and his family are trapped in false class consciousness, forming a vicious cycle similar to that experienced by Biff and Willy, where individuals feel perpetually “trapped”.

There are, however, challenges to this mode of thinking throughout the film, most notably the existence of the Dead Poets Society and the final scene. This is reinforced through the social unity among the Dead Poets. Muro notes that “they act as a group… they support Neil in his struggle against his father… accept Todd’s shyness… and turn against Cameron when he betrays Mr. Keating”. Another subtle rebellion occurs when Neil encourages Todd to throw the “aerodynamic” desk set and let it “fly”. This can represent rebellion against Todd’s absent parents, as well as Neil’s own yearning to break free from his overly present ones.

The imagery of the Dead Poets’ nightly journey to the cave recalls Sylvia Plath’s poem Mushrooms:

Overnight, very

Whitely, discreetly,

Very quietly

Our toes, our noses

Take hold on the loam,

Acquire the air.

Nobody sees us,

Stops us, betrays us;

The small grains make room.

Soft fists insist on

Heaving the needles,

The leafy bedding,

Even the paving.

Our hammers, our rams,

Earless and eyeless,

Perfectly voiceless,

Widen the crannies,

Shoulder through holes. We

Diet on water,

On crumbs of shadow,

Bland-mannered, asking

Little or nothing.

So many of us!

So many of us!

We are shelves, we are

Tables, we are meek,

We are edible,

Nudgers and shovers

In spite of ourselves.

Our kind multiplies:

We shall by morning

Inherit the earth.

Our foot’s in the door.

Though written in a different context, the poem conveys a similar meaning: rebellion against societal structures in the quiet of the night. The mushroom symbolises decay and life simultaneously, fitting the very name Dead Poets Society, which encapsulates both tragic inevitability and resistance. Hentzi argues that the Dead Poets represent a new-age thinking, “it should therefore come as no surprise that some of its most fervent adherents are well-educated urban dwellers”. However, McLaren counters that these rebellions are subtle and largely powerless: “Resistance is reduced to idiosyncratic acts of bourgeois transgression, performative moments of apostasy without the benefit of critical analysis.”

In the original screenplay, the poem “Little Blue Boy” by Eugene Field was also meant to be referenced. This poem arguably foreshadows Neil’s fate, as “the little toy friends” are left wondering “in the same old place… what has become of” the Little Blue Boy. Neil, having reconvened the Dead Poets Society after 25 years and discovered his passion for acting, is ultimately forced to leave, much like the Little Blue Boy who has to grow, highlighting the inevitability of Neil’s fate. This leaves his dreams for himself in an eternal state of limbo — one that can never be achieved, only felt. In the end, he becomes the “old lady” with a “passion for jigsaw puzzles” who finds herself in “the center of the puzzle”, defeated by a “demented madman”. As Neil discovers acting and his passion for it, he also realises the morbid reality of his life, and how he would never be able to reconcile with his identity in the current society, which represents the madman.

Broader view

DPS has left a significant mark on modern cinema. On the first enactment of DOAS, visitors noted that there were members in the audience who simply “couldn’t stop crying”. This was followed by many other audiences, across different generations. DPS falls within the same line of stories that resulted in a violent, unstoppable spree of catharsis. There is something about the common narrative thread between these two storylines that immortalises them and moves audiences to such an extent that makes them unforgettable and timeless. Is it the notion of the American Dream? Is it that dream failing its tragic heroes? Is it how morbidly realistic these stories are to our everyday lives? Is it the tragedy of the common man? Or is it the yearning for something similar?

Different audiences are impacted differently, and by different parts of the stories. It is hard to determine what exactly it is that moves the audience. But one thing is for sure: both stories are stories for the people — not for an unrelatable elite, and not for historical royalty. DOAS represents sections of society who will never be more than a “salesman”, and who will never find their place within this unattainable American Dream. DPS is relatable for those who yearn to find community, unleash creativity, romanticise nature, and “seize the day”. There is nothing radical in wanting belonging — which is what both these stories show. It becomes radical because we live in a society where alienation has become more normal than purpose.

There is cinema that leaves you wishing you were a part of that life, where everything has a happy ending and all challenges are guaranteed to be resolved. Then, there is cinema that forces you to reflect on your own life and inspires you to do something about it. DOAS and DPS clearly fall in the second category. This is why the stories resonate so much with the audience; they are not seen and then forgotten — they are experienced and learned from. Watching DPS at 17 is a completely different experience than watching it again at 40. These are stories that grow and evolve with you, shaping the decisions you make and the values you inhabit. These are the stories that, I believe, highlight the very importance of cinema. In Ethan Hawke’s words, this is when “art’s not a luxury, it’s actually sustenance”. It forces you to reflect on your own humanity — who are you beyond societal terms?

Cinematography

DPS is a movie that speaks to the very soul of the ordinary man. To an average audience, a film about classical poetry is not even considered a movie. Yet, Peter Weir’s DPS has certainly proved that wrong. Poetry through film is itself a revolution. One thing I noticed about the film is that it presents poetry in motion. The way it is filmed — the setting, diction, soundtrack, costumes, and camera shots — all come together to give motion to poetry, making the film itself an unconventional work of poetry.

The first time we see Neil interact with his father is through Todd’s perspective, as the camera focuses on him unpacking while the discourse about leaving the school annual happens in the background between Neil and Mr. Perry. This clearly establishes the juxtaposing character arcs between the two dynamic characters: Todd Anderson and Neil Perry. While Neil is burdened by the overbearing and controlling presence of his father, Todd could only wish his parents cared enough to be actively present in his life.

The flow and movement of the camera in DPS highlight and reinforce the key motifs throughout the film. The most notable and memorable shot is perhaps when Todd faces his fear by reciting an improvised poem, encouraged by Keating. John Seale directs the camera to rotate around Keating and Todd, picking up pace until the rest of the class turns blurry and the audience is drawn into Todd’s world and perspective. As the camera rotates rapidly and close to Todd’s shoulders, the film forces us to experience Todd’s anxiety and how he overcomes it through poetry. This serves a literary purpose as well, as it builds a stream of consciousness, where the artist is at full creative freedom to produce a raw piece of art. The cinematography used here matches the pace of the poem Todd recites: slow at first, as he explores the imagery of the “sweaty-toothed madman”, then progressively faster as he adds action to the poem, before slowing into stillness again as he dramatically concludes with the final gothic lines: “from the moment we enter crying, to the moment we leave dying, it will just cover your face as you wail, cry, and scream”. This establishes poetry as a moving object, amplifying its power.

The film also alternates between still and moving shots. The still shots, as highlighted by Jackson Barnes, occur mostly when characters are burdened and stifled by the bureaucratic expectations of Welton and their parents. The moving camera shots take place as characters begin to establish their individuality and rebel against societal structures. The movie begins with a still shot of a mural. The original screenplay describes the scene as: “On the left is a life-sized mural depicting a group of young schoolboys looking up adoringly at a woman who represents liberty. On the right is a mural showing young men gathered around an industrialist in a corporate boardroom.”

The purpose here is clear. The schoolboys can be interpreted as innocent, naïve sections of society who look up at “liberty”, which, to Welton, is the American Dream. According to Welton, they achieve this on the right, in an industrialist setting. However, under the romantic lens of the film, this serves as a critique of the American Dream, with liberty representing free thinking and artistic endeavour rather than impersonal corporate rooms.

The first time we see Neil and his father together is in the audience — again, a still shot. This establishes the tension and troubled dynamic between the two: Neil, careful not to disappoint his father, and Mr. Perry, full of hope and hubris.

This stiffness is juxtaposed with scenes where Neil aligns with his creative purpose. For example, when Neil first finds out about the play and talks to Todd about it, the camera follows Neil as he rushes around the room, pounds on the bed, and tosses papers into the air. Besides indicating Neil’s creative fulfilment and identity, this shot establishes him as a natural leader, beckoning the camera with his movement. The dynamic shot that follows, where Neil grabs Todd’s notebook and runs around the room, suggests the innocence that exists between them when they are not stifled by autocratic forces. This serves a thematic purpose by showing how seventeen-year-olds should act — not burdened by the future, but free in the present.

The happiness of these moments is short-lived and is always undercut by scenes where Neil must face his father. This can be seen when Mr. Perry makes a surprise entrance after discovering the play. Though Neil enters jovially, the camera quickly becomes still again as Mr. Perry confronts him. The camera then slowly zooms into Neil’s face, symbolising both his oppression and his realisation that his father will never see him for who he truly is. This technique of zoom happens in almost every scene where Neil feels ‘trapped’.

This is the same fate he resigns himself to before his death. Though Neil stands up, the shot remains still and confined, highlighting his helpless position and evoking pathos and suffocation even within the audience.

Cinematography in DPS also reinforces the juxtaposing character arcs of Neil and Todd. After Neil’s death, the camera widely follows Todd as he runs into the purity of the snow, falling in the process and letting out his first “barbaric yawp”, which is Neil’s name. McLaren observes that Todd’s vomiting is his body’s “rejection of what his social conditions have made of him: a docile body. After the discharge, Todd runs away wildly… finally letting out his barbaric yawp.” This marks a clear turning point for Todd and the moment he breaks free, as the camera now follows his lead instead of Neil’s, establishing Todd as the new leader.

This idea is reinforced in the final scene, where the camera follows Todd as he rises and stands on the desk. This encourages others to stand as well, and the camera captures the divided classroom before concluding heroically with Todd’s close-up.

Social Protest

Another reason DPS has become timeless is because it offers a social protest against ideas passed down through generations. For instance, although women are treated as props in the film, this can be interpreted as a form of protest that highlights the very loss of autonomy women faced in the 1960s, creating a layered narrative.

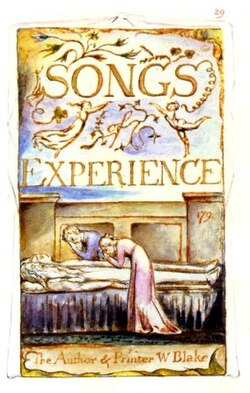

A key Romantic poet was William Blake. Many of his poems, particularly those in Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, protest similar notions — such as The Chimney Sweeper, The Little Lost Girl, and London. These works echo criticism of capitalist greed, the abuse of nature, organised religion, and rigid tradition. The Chimney Sweeper, in particular, highlights the exploitation of children by adults. Though written in a different context, it remains relevant to both contemporary society and the one portrayed at Welton in DPS. Blake protested against children being treated as adults, arguing instead that childhood represents innocence and enlightenment rather than ignorance, resulting in harmony with God and an egalitarian society.

This notion is evident in DPS, where students are rigorously trained to satisfy capitalist demands, stripping them of youthful innocence and creativity. Parents project their own negative experiences onto their children, a fear skilfully exploited by Welton to produce another self-indulgent force for wider society, entrapping students — the chimney sweepers — in a vicious cycle. Nietzsche’s “God is dead” philosophy can further be applied here:

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us?”

This suggests that the concept of God, as the ultimate source of meaning, morality, and truth, has lost its power in modern culture due to science, reason, and individualism, creating a state of nihilism where traditional values crumble and humanity must create new ones to avoid despair.

This is reflected in DPS, most explicitly when Neil introduces “the God of the cave”. Removed from religious fundamentalism and Welton’s rigid bureaucracy, the Dead Poets create their own values to prevent despair in a society that prioritises science and reason over mortality and purpose.

Today’s audience differs from those of the 1950s, when DOAS was first enacted, or the 1990s, when DPS initially screened. Yet modern audiences continue to resonate with both stories, suggesting that society remains trapped in the same vicious cycles they protested against. The American Dream still exists, remains unattainable, and shifts every time one nears it. This destructive pursuit leads to a slow descent into madness and fatalism. Systems have long sustained themselves by creating problems and then marketing solutions to them.

Neil represents those trapped between competing societal systems — and their consequences. DPS delivers a fatal message: Neil, as a student, symbolises innocence and naïveté, abused and neglected by the very adults meant to protect him. Gage argues that Dead Poets Society reveals that both utilitarian and romantic ideologies commit the same sin — “strip-mining poetry to use its riches for selfish purposes while ignoring the higher beauty it points to”.

The message of DPS is not to revolt or dismantle society, but to assert that following one’s purpose should not be revolutionary. Free, creative thinking should not be radical or restricted to elites, nor hindered by economics. “We are dreaming of tomorrow and tomorrow isn’t coming… and still we sleep.” This is why DPS resonates across generations: it shows audiences their potential, then grounds them in bleak reality, but not without offering a lingering hope for the future.

Snapper also connects Keating’s pedagogy to contemporary UK education, particularly A-level teaching. He argues that “we want authentic responses from students, yet we often circumscribe them in unhelpful ways”, excluding meaningful exploration. He notes that students frequently “lose sight of the life that the texts they study have outside the classroom”, and that assessment often sends “mixed messages” about expected responses. The role of English teachers, he believes, is to teach students “to love literature”. This is contrasted with the current trend, where “far from being passionate about poetry, many of them feel alienated from it”. He concludes that there is a need to “resolve some of these tensions through a careful reflection on what English Literature A Level is for”.

This highlights the cinematic power of DPS: it exposes flaws in modern education systems. Personally, my English Literature teacher closely resembled Keating by being just as passionate and inspiring. She once encouraged me to realise my potential by pursuing what I feel called towards, reminding me that I was too young to have regrets, and therefore didn’t have to worry about making any irreversible mistakes. For me, this precisely answers Mcallister’s and Nolan’s concerns about encouraging free thinking at seventeen. This age may, in fact, be the most important time to develop independent thought and creativity, long before “Carpe Diem” becomes wishful nostalgia. Cutting students off from destructive cycles early sustains creativity not only individually, but societally. As the Bhagavad Gita states, “it is better to do one’s own duty imperfectly than to do another’s duty perfectly”.

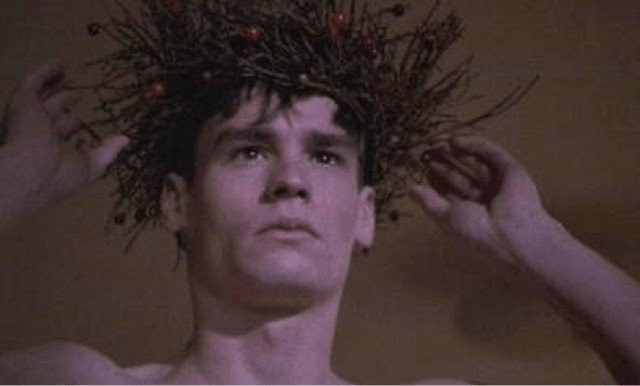

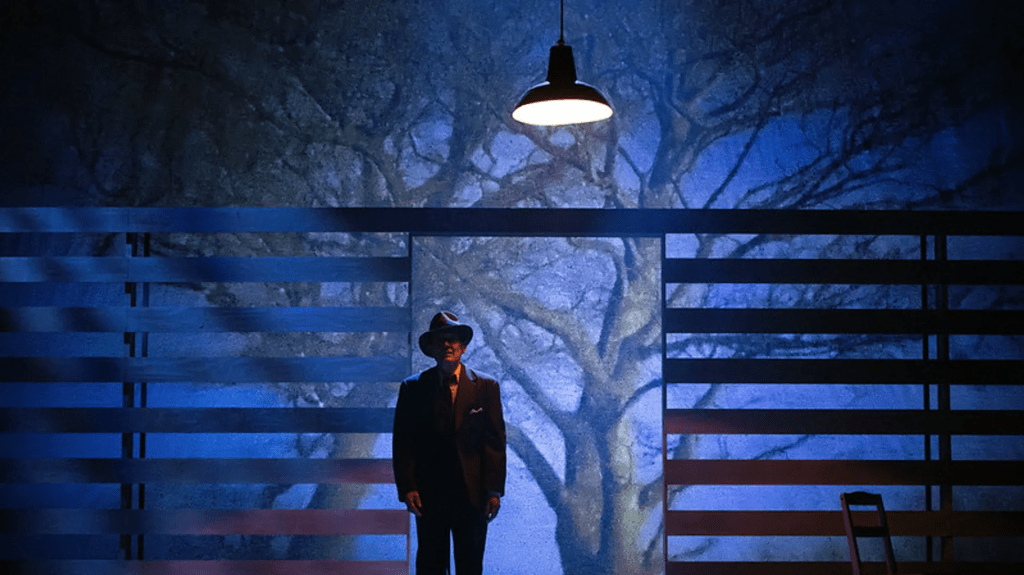

I would like to conclude with my favourite frame from Dead Poets Society.

I believe this single frame sums up the nuance surrounding Dead Poets Society. It highlights the simplicity of life, where both characters are fulfilled by their own purposes and remain in harmony with nature. Though idealistic, the image becomes foreboding when we consider the fate awaiting them, especially in regards to the contrast in lighting. As Whitman asks: “The powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?”

References

Jackson Barnes, ‘Dead Poet Society: How Cinematography Conveys Theme’ (http://www.youtube.com) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1pi3wOojbkE> accessed 3 January 2024

Refractions, ‘Dead Poet’s Society (1989)’ (One Shot7 October 2014) <https://refractionsfilm.wordpress.com/2014/10/07/dead-poets-society-1989/>

Anderson A, ‘“Chased by Walt Whitman” Or, Why Did Neil Perry Kill Himself?’ (Medium10 August 2020) <https://medium.com/@adelynnanderson/chased-by-walt-whitman-or-why-did-neil-perry-kill-himself-9d4fdcdf2c49>

‘In Defense of Dead Poets Society’ (Bright Wall/Dark Room4 April 2016) <https://www.brightwalldarkroom.com/2016/04/04/in-defense-of-dead-poets-society/>

Adam Kirsch, ‘“Dead Poets Soci Ety” and Artis Tic Expression’ (2022).

Bauer DM, ‘Indecent Proposals: Teachers in the Movies’ (1998) 60 College English 301

Muro A, ‘“What Will Your Verse Be?”: Identity and Masculinity in “Dead Poets Society”’ (2018) 16 Journal of English Studies 207

Bronner S, ‘Chapter Title: The Problem of Tradition Book Title: Following Tradition’

Callahan T, ‘Devil, Trickster and Fool’ (1991) 17 36

Mitchell, N. (2022). Carpe Diem: Why Dead Poet’s Society is the most important coming of age movie ever.

Collins, M. (1989). Instructional materials: Make-Believe in Dead Poets Society. The English Journal, 78–78(8), 74–75. https://www.jstor.org/stable/819492

Dead poets do tell tales. (1995). The English Journal, 84–84, 84–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/820593

McLaren, P., & Leonardo, Z. (1998). Deconstructing Surveillance Pedagogy: Dead Poets Society. Studies in the Literary Imagination, 127–147. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1124&context=education_articles

Giroux, H. A. (1993). Reclaiming the social: pedagogy, resistance, and politics in celluloid culture. In Counterpoints (pp. 35–58) [Journal-article]. Peter Lang AG. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45136431

Hentzi, G. (1990). Peter Weir and the cinema of new age humanism. In Film Quarterly (Vols. 44–44, Issue 2, pp. 2–12). University of California Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1212654

Hermeneutical analysis of the film Dead Poets Society. (2018). International Journal of Media and Information Literacy, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.13187/ijmil.2018.1.3

Scull, W. R., & Peltier, G. L. (2007). Star Power and the Schools: Studying Popular films’ portrayal of educators. The Clearing House, 81–81(1), 13–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30189946

Rumaria, C., R. (2015). AN ANALYSIS OF SPEECH ACTS IN THE DEAD POETS SOCIETY. In A THESIS Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Attainment of the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education.

Beyond Dead Poets Society. (2006).

Dead Poets’ Society: Teaching, Publish-or-Perish, and Professors’ Experiences of Authenticity. (2006). In Symbolic Interaction (Vol. 29, Issue 2, pp. 235–257). Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction.

Gage, J. R. (2024). The unintended brilliance of Dead Poets Society. In lawliberty.org. https://lawliberty.org/the-unintended-brilliance-of-dead-poets-society/

Leave a comment